As the holiday season approaches, people across Canada are struggling to navigate the new risks that come with following family traditions in this unprecedented time of COVID-19.

While many government health officials are telling Canadians to stay home for the holidays, there isn’t a universal, hard and fast rule that applies to traveling this December.

- The Cost of Living ❤s money — how it makes (or breaks) us.

Catch us Sundays on CBC Radio One at 12:00 p.m. (12:30 p.m. NT).

We also repeat the following Tuesday at 11:30 a.m. in most provinces.

There are a lot of choices to make, from travelling to visiting family to sharing meals, all of which are impacted by the changing COVID-19 infection numbers in each region of the country. For those struggling with how to make up their minds, CBC Radio’s The Cost of Living tracked down an economist who developed a five-step process to help you make hard decisions when you don’t have enough data.

Data-driven parenting advice led to COVID questions

Just before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, economist Emily Oster started a newsletter for parents about how to interpret data and how to think about decisions in pregnancy and parenting.

The professor of economics at Brown University in Rhode Island also writes data-driven books on those subjects, and found that as the pandemic began, she was getting more and more questions about it.

“As COVID was happening, people were asking me all the time, how can I make these decisions about COVID? Should I see my parents? Should I send my kids to child care? What should I do about groceries?” said Oster.

Oster said her inbox was overflowing in the spring, with similar questions coming up again and again. In particular, she was being asked about how to safely interact with parents or grandparents and how to deal with child care.

In a household of economists, data drives every decision

The sheer volume and specificity of emails forced Oster to ask herself “well, how am I making these decisions in my own life?”

“Full disclosure, both my parents are economists,” Oster admitted with a laugh. She was still in college when she said she realized she was destined for a career crunching numbers. An “ill-fated” summer working to dissect fruit fry brains may have contributed to the decision after she compared that position to working for an economist.

“I was like, well, one of these is more up my alley,” said Oster.

Years later, with two kids and a partner who is also an economist, Oster said her decision-making process evolved out of asking herself: “how can I talk about how my family tries to put structure on these choices?”

Those choices included whether she should send her kids back to school in September.

When Oster published her five-step-system on her blog, her goal was to be “a little more explicit about how you might think through those choices, kind of reflecting the way that we do it in a household with many economists.

Why COVID questions are so difficult to answer right now

The tremendous uncertainties of 2020 have complicated even the most basic decisions, according to Oster.

“When I write things for parents, like ‘how important is it to breastfeed? For how long?’ There’s a lot of data on that,” said Oster.

The amount of information we have is so limited and it is changing all the time … yet the decisions have to be made now.– Emily Oster, economist

“It doesn’t mean that the answer is obvious, but when you are talking to someone about that, you say: ‘Here is this study. Here is this data. Here is what we know about it. Here is all the previous millions of millennia of information about this topic,’ and you can talk through all that.”

With COVID-19, there isn’t enough data available yet to go through the same process.

“The amount of information we have is so limited and it is changing all the time,” said Oster.

“Yet the decisions have to be made now. So we’re kind of faced with a situation where we have to make a lot of decisions, knowing that there will be a lot of uncertainty remaining after you make the choice and knowing that you’re going to have a hard time feeling really good about any of this.”

Oster went through her five-step process to make decisions in the face of uncertainty for The Cost of Living

Step one: Frame the question

According to Oster, start the whole process by framing the question.

“Write down or think about or articulate what exactly are the choices that you are deciding between. What do you see as the options?” said the economist.

It seems straightforward but many people don’t actually consider the alternative to the choice they are making, said the economist.

For example, Oster heard from many people asking, “should I send my kid to daycare or not?”

But she said those same people were not thinking about what “or not” actually looks like for their family.

“The kid doesn’t vanish,” said Oster.

“They will need to do something. Is ‘or not’ stay home with you? Is ‘or not’ have a nanny? Is ‘or not’ send them back to school in two weeks?”

Framing the question means sitting down and thinking about the actual options you are choosing between.

Step two: What are the safest ways to complete those options?

Once you’ve framed the question and identified your options, step two is figuring out how to make each option safe for you and your family.

“In the COVID world,” Oster said you have to,”think about how you can do these things as as safely as possible.”

We now have a lot of information about which activities are safer, such as many outdoor activities at a distance.

Step two involves brutal honesty, asking yourself: what is the safest possible way to do this?

For example, asking how much can the risk of seeing parents be mitigated? Can a visit be outside? How risky is that?

Step three: Evaluate the risks

Now that you’ve identified and hopefully mitigated the risks involved in your choices, step three is to assess the risk level between those two options.

“Okay, now I know the safest way to do Option A and the safest way to do Option B,” said Oster.

If you are deciding to visit elderly grandparents, for example, Oster said there are a number of risks to evaluate.

“That involves both the risk of transmitting COVID, [it] involves the risk of serious illness,” said Oster.

“Do you have an immune compromised person? Are you just two healthy adults and two small children, where the risks are much are much lower?”

Step four: Think about the benefits

So far COVID-19 has forced us to consider a lot of serious and (sometimes) scary realities about our options.

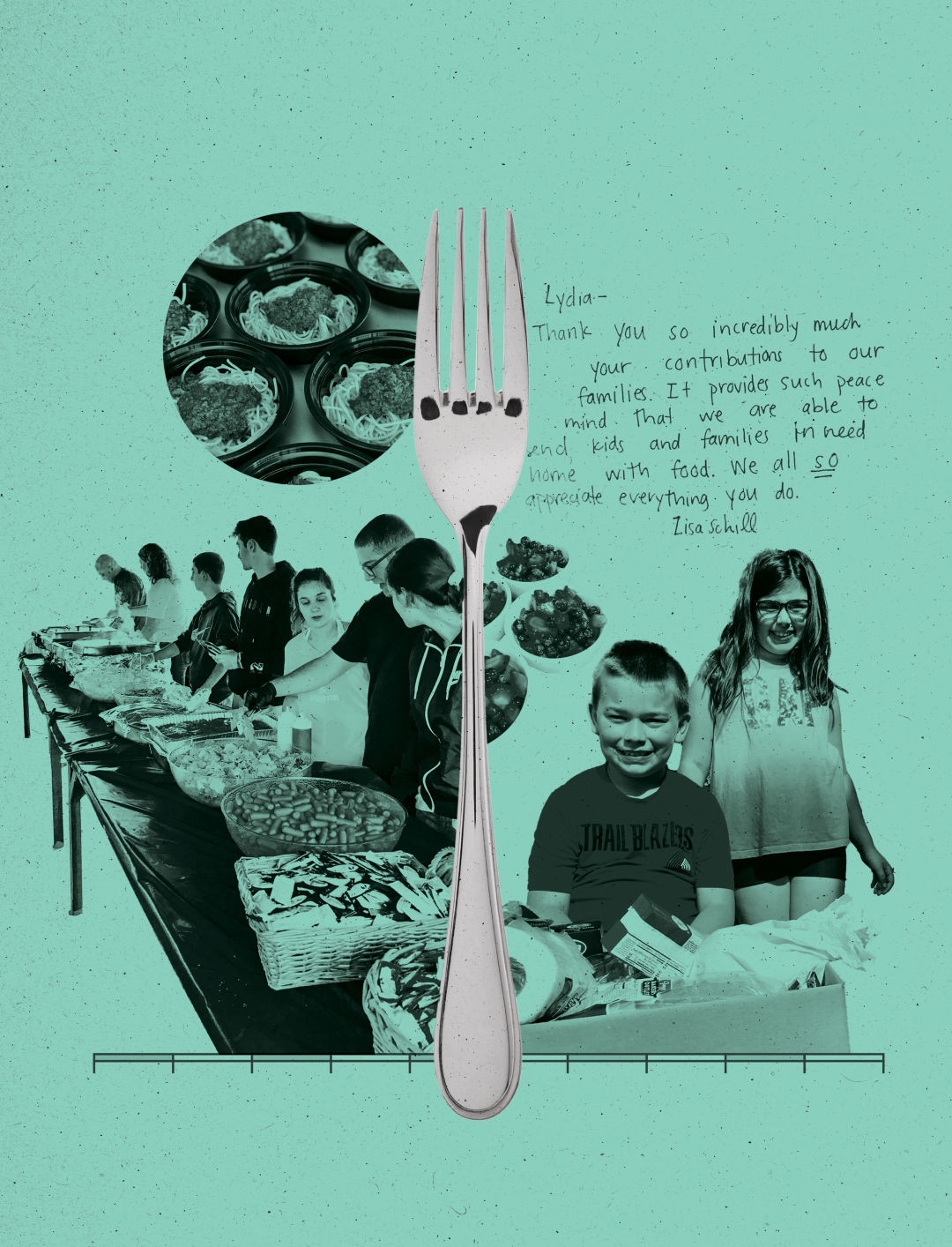

But step four is here to remind you that there are also very real benefits to seeing family and following traditions.

“This is an important step because there are real benefits to a lot of these choices,” said Oster.

“It is important to be very careful about COVID, but it’s also important to think about some of the risks on the other side.”

Oster said to include things like the mental health risks associated with isolation, the work time you may lose if you’re trying to educate your children at home due to quarantine or self-isolation requirements, and the mental health issues children may experience as a result of this unprecedented time.

Step five: Decide

The final step in this decision-making process is to decide, which Oster admitted may seem quite basic.

“Of course the last step would be to decide, that’s what you have to have to do. But I actually think [that] because these decisions are so hard, people have been letting them take over indefinitely rather than saying, ‘I am going to sit down and make this choice and then try to move forward,” said Oster.

- Don’t feel like waiting for your dose of The Cost of Living on Sundays?

To listen anytime, click here to download the show to your podcast player of choice.

Subscribe to get episodes automatically downloaded to your device.

According to Oster, you need to make a decision and then try to stop thinking about it. Making a choice can give a sense of closure, even if the final decision doesn’t feel great.

“Try to implement the decision. Realise maybe you’re not going to feel great about it, but just decide that you’ve decided and then try to move on.”

Written and produced by Tracy Fuller.

Click “listen” at the top of the page to hear this segment, or download the Cost of Living podcast.

The Cost of Living airs every week on CBC Radio One, Sundays at 12:00 p.m. (12:30 NT).

More Stories

‘Hack Your Life’ Allows Pupils with Health, Teachers – News

Eat purely natural, household-cooked food items to make immunity: Nutritionist Manjari Chandra

50 Lifehacks for Building Resilience | Write-up